How old is Jeffreys St?

Plans to build this street were drawn up in the 1790s but the first four houses on Jeffreys St were completed in 1816. Most of the others by the early 1820s and the last group on the south (even) side were added in the 1840s.

Where is this information from?

Our houses pre-date the online Census but there are still reliable records we can look up. The first person to document when a new house was complete and inhabited was the tax man. Camden Local Studies Library in Holborn has all of the tax (poor relief) records for our parish so we can look to see when each of our houses was built and who first moved in. (Start with Utah Microfilm no 542-593 for St Pancras Parish North). Jeffreys Street does not exist before July 1816 and then just four houses are documented.

On the north (odd) side:

Current house numbers 25, 27, 29 and 31 were built and inhabited by July 1816

17, 19, 21, 23 and 33 by January 1818

13 and 15 by January 1820

1 and 11 by September 1821

3,5 and 7 by January 1823,

9, 35 and 37 were complete and inhabited by July 1825

Philia House was built in the 1980s on the site of an Esso garage, which was itself built on the site of bomb-damaged gardens of former large houses on Royal College St.

On the south (even) side:

2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 and 20 were all completed by autumn 1825

Number 2 is currently named 10 Prowse Place

22 and 24 by March 1844

26 by March 1846

28 by March 1847

30 by September 1848

Jeffreys Street is the link between Camden and Kentish Town - one of the first streets built to form the new Camden Town and also one of the first lateral extensions of the older Kentish Town Rd.

The site on which Jeffreys Street was built

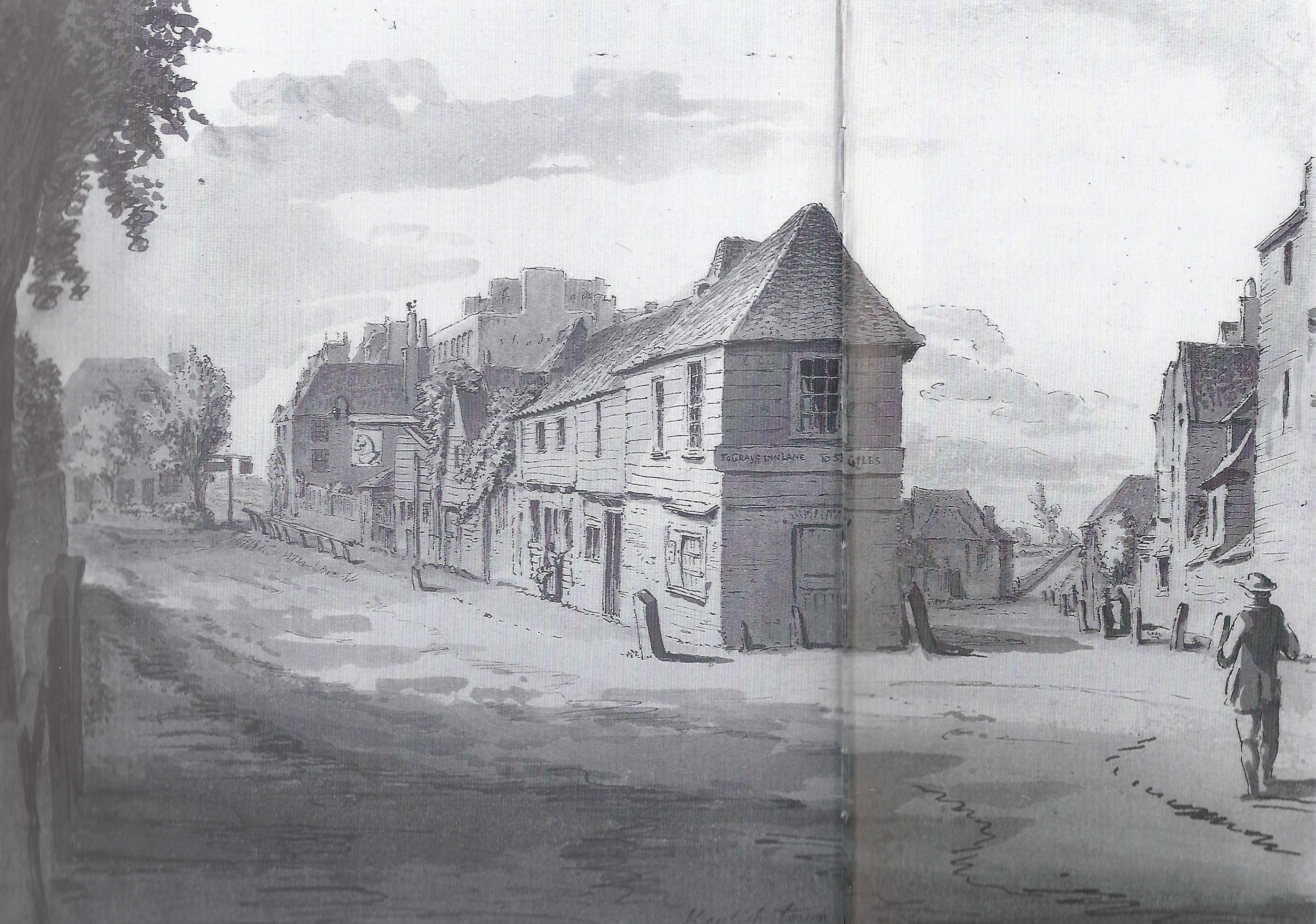

This is an image of what the field looked like just before Jeffreys St was built. JF King drew this panorama of the whole of both sides of Kentish Town Rd. Some parts were drawn from memory with a little artistic license but his drawings of Kentish Town largely match the J Thompson map of 1804 which was one of the most accurate of its day, as can be seen when you see it overlaid with a modern Google Map (right). In 1804, the main heart of Kentish Town ended at the boundary garden wall where Farrier St runs today. Jeffreys St was built on virgin green field, named Lower and Upper Barn Field. Both King's Panorama and J Thompson's map are available to view in hard copy only from Camden Local Studies Library on Theobalds Rd.

J Thompson's map showing the site of Jeffreys Street 12 years before the first houses were completed. Below, a plan from 1810 from the Crace Collection of Maps of London shows Jeffreys St laid out, but not yet built. Greenwood's 1827 map of London beneath this shows Jeffreys St almost complete.

What was it like here for the first residents?

A rural Georgian country town

To summarise Gillian Tindall’s excellent The Fields Beneath - do buy a copy from Owl if you haven't already - when Jeffreys St was built, Kentish Town was a village starting to have the look of a Georgian country town, but still had un-paved village roads and poor drains. It was good farm land, famous for its healthy fresh air – but you could sometimes smell the brick kilns nearer St Pancras Old Church.

Jeffreys St had a view across the Quinn's junction at unspoiled marshes and out the other end of the street of waving grassland and fields studded with cows. Camden Road wasn’t there and the view was of lush grassland, getting progressively more boggy as it neared the old St Pancras church.

Charles Dickens at his desk

Streets of Camden Town by the Camden History Society adds that in the 1820s, Charles Dickens was living in Bayham St with his parents. The Regents Canal had just been built (1814-16) and Camden Road was authorised by an Act in 1824 and started to be built two years later.

What would it have sounded like when you opened the windows?

RSPB Conservation Manager Michael Copleston says when our houses were built, the surrounding wet grassland would have been teeming with birds. He lists curlews and lapwings calling over the fields; snipe drumming and, nearer the farmland, the sound of quail, partridge and possibly the night time call of corncrakes. The new gardens would have seen yellowhammer, whitethroats, black caps, chiff chaffs and corn buntings amongst those you might expect to find now, such as robins, dunnocks and sparrows.

What had people said about the area?

A lovely picture of our surrounding neighbourhood is painted in Gillian Tindall’s The Fields Beneath:

Healthy fresh air

“As early as 1725 the idea that one came to Kentish Town for one’s health seems to have been currant”. Antiquarian Rev Dr Stukeley wrote “I found a most agreeable rural retreat at Kentish Town…. Tis absolutely and clearly out of the influence of the London smoak, a dry gravelly soil, and air remarkably wholesome.”

Rural Beauty - 1830s

“James Hole, a housing reformer…wrote in 1866 ‘The inhabitant whose memory can carry him back thirty years recalls pictures of rural beauty, suburban mansions and farmsteads, green fields, waving trees and clear streams where fish could live’.”

Waving grassland - 1810

“When Thomas Milne drew up a detailed Land Utilisation Map of the London Area, virtually all the land in the parish and in neighbouring Islington was grassland, except for a few nursery gardens and orchards.”

Stray animals

“Picturing a neighbourhood at any date before about the accession of Queen Victoria, one should remember the ubiquitous presence of animals; apart from the horses and cattle enclosed – or supposed to be enclosed – in fields, there would always have been single cows and goats browsing on the wide ‘waste’ by the side of the road, or pastured on the common land.”

Streets of Camden Town by the Camden History Society adds “Farms in the area provided milk for the metropolis and hay for the capital’s horses.”

Fertile soil for gardeners – since 1186

“In 1186 the propagandist FitzStephen wrote … that the St Pancras district had ‘cornfields, pastures and delightful meadows, intermixed with pleasant streams, on which stands many a mill… The cornfields were not of a hungry, sandy mould but as the fruitful fields of Asia, yielding plentiful increase and filling the barns with corn… Beyond them, a forest extends, full of the lairs and coverts of beasts and game, stags, bucks, boars and wild bulls’.”

A bit wet and marshy – even in 1350s

“An Inquisition taken on Tottenhale manor, lying west of the Fleet in 1350, paints a picture of… ten acres of Marsh Meadow worth 5 shillings by the year and no more, because they were overflowed and could not be mowed, except in a dry time.”

Where was the heart of Kentish Town?

The Castle Tavern

From the late middle ages to the mid sixteenth century Kentish Town “securely established itself near the fork at the Castle Inn.” Inhabitants of Kentish Town had left the medieval settlement amongst the most marshy reed beds by St Pancras Old church and taken themselves “to the higher, drier land… where by now another road (Tottenham Court – Hampstead Road) joined the Kings highway Just north of this junction. Where the Castle Inn was and is today, the new Kentish Town established itself, and there it has remained – except that a slight drift further northwards becomes apparent in the nineteenth century, and was confirmed by the siting of railway and underground stations.” (The Fields Beneath)

The view down Kentish Town Road and what is Royal College Street today, before 1886

“A huddle of ‘poor cottages’ at the fork by the Castle had been removed in the 1890s, but this was part of a road-widening scheme. They were replaced by blocks of the ‘model dwellings’ variety.” (The Fields Beneath)

How Kentish Town took shape

Kentish Town was really just one long street. “A commentator Aiken, writing soon after (1800), remarked that ‘the hamlet of Kentish Town consists of a long street ascending to the high ground near Highgate and chiefly composed of boxes [holiday houses] and lodging houses for the accommodation of the inhabitants of London, with boarding schools, public houses etc’.”

“The very detailed map of 1796 [J F King’s Panorama]… shows the road from a little below the Castle northwards as far as Batemans’s Folly at the foot of Highgate Hill entirely fringed with properties of one kind or another, though many are spaced out with gardens or paddocks in between. The first lateral development – Mansfield Place (now Holmes Rd) and Spring Place had also appeared.”

There was a “general building boom between 1816 and 1826. Some of these developments led off … at right angles to the high road… but most were in-filling developments lining the main road.” (The Fields Beneath)

Pang's: one of the oldest buildings in Kentish Town

Jeffreys St was one of these.

A handful of the late 1700s buildings in J F King’s Panorama still stand. One of which is the building that houses Pang's fish and chip shop, turned sideways to the road. Later buildings always fronted the main road.

Kentish Town: not really part of London yet but well connected

“The fields behind the new terraces might still be as rural as ever, sprinkled with cows and barns, but they were no longer visible to the passing traveller. Instead he saw rows of pedimented, stuccoed facades as uncompromisingly urban as any in the new planned developments like Bloomsbury… Yet places like Kentish Town, still improperly paved and lighted and innocent of drainage, were not really part of the town yet; the houses along the main roads were in every sense a façade”. (The Fields Beneath)

Streets Of Camden Town adds: “Although the road was still unpaved and mostly unlit in 1800, there were hourly coaches to London from Kentish Town, and by 1820 the service had increased to seven coaches, between them making up to 50 journeys a day.”

The rest of Kentish Town and Camden is largely Victorian. “Between roughly 1840 and 1870, Kentish Town was substantially altered from a suburban village, surrounded by fields, into the townscape we see today.” (The Fields Beneath)

The River Fleet

From Hampstead Heath via Hampstead ponds the Fleet “proceeds through Kentish Town… till it crosses the lower part of Kentish Town Road below the Castle Inn, at almost the same place where the Regent’s Canal has run since 1820. But just before making this cross to the eastern side of the road it is joined by its other main tributary…. Today from the Highgate and Hampstead ponds onwards, it is encased in cast iron pipes the whole way to the Thames.“ (The Fields Beneath)

Gradually, as the eighteenth century progressed, more and more of the Fleet River was arched over.

Water Lane now branches off Kentish Town Rd

“The Fleet was still open just north of St Pancras Old Church, but a large segment disappeared underground when the Regent’s Canal was constructed…. It was still capable in 1820 of causing floods in the Kentish Town area, principally at the point where it crossed under the lower part of what is now Kentish Town High Road and what was known for centuries before as ‘Water Lane’.”

Streets of Camden Town by the Camden History Society adds: “Kentish town Rd was long known as Water Lane, (or sometimes Old Watery Lane), from the flooding of the River Fleet, which used to cross over the road here. King says the roadway was very narrow, ‘not passable for man nor beast’ because of the frequent overflow of the river... In 1826 the Fleet in flood was 65ft across at this point. “

What was happening elsewhere at the time?

By 1815 Britain had been funding an expensive war with France almost continuously for 22 years.

Wellington had defeated Napoleon at Waterloo so the war was over but the financial strain and large numbers of returning soldiers created mass unemployment, a recession and a housing slump.

In 1816 the Prime Minister was Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool. George III was King but his son Prince George had been ruling since 1810. (So we’re around Blackadder III for those with a keen eye for history)